People generally don’t like taxes, and taxes on gasoline are no exception. The rates on gasoline taxes are generally hidden from obvious view: people buying gas for their vehicles only see the price at the pump, which is a function both of tax rates, and the fluctuating price of wholesale gasoline. Most people have no idea what portion of what they’re paying is tax and what portion reflects fluctuations in market price.

Can you remember when gas was this cheap? Can you remember when Sohio had not yet been bought by BP?

What is the current gas tax rate in the US?

In the U.S., unlike sales tax which is a flat percentage, gasoline is usually taxed at a fixed rate of cents per gallon. There are both state and federal taxes, and a few local ones as well. The federal gas tax is currently 18.4 cents per gallon for gasoline and 24.4 cents per gallon for diesel. The USDOT Federal Highway Administration has an excellent history of the federal gas tax on their website.

State taxes vary widely, and the taxes on diesel vs. regular gasoline also vary. Unfortunately, I was not able to locate current figures on individual state tax rates, in one page whose figures I trusted. The lowest tax rate is in Alaska, and the highest in New York State. The average total gas tax is around 50 cents per gallon in the U.S. For gas of about $3/gallon, this tax constitutes about 1/6th or about 17%.

The current gas tax is not high enough to fund road construction and maintenance:

Although federal gas tax revenues (and some states’ as well, including Ohio) are set aside mostly for road construction and maintenance, the current rate is too low to even pay for road maintenance. Real Clear Markets published an article A Good Grade on a Possible Gas Tax in October, which points out that the federal gas tax has remained at a fixed rate since 1993. The tax is not adjusted for inflation, nor does it rise as the price of gas rises over time. The result is that the inflation-adjusted price of the tax has fallen, and the rate of tax as a percentage of gas prices has fallen even more. However, road spending as a proportion of total government spending or revenue has not decreased. This means that more funds have been transferred from other taxes and other government budgets being used for road construction and maintenance, thus contributing to the budget deficit.

Positive and Negative Impacts of High Gas Prices:

Before I propose my idea for a gas tax, I want to emphasize that high gas prices have both positive and negative effects on society. The negative effects are obvious; most of the negative effects of high gas prices are felt immediately:

Negative Impacts of High Gas Prices:

- High gas prices dampen economic activity, because much of this activity depends on vehicles that use gas, including travel and shipping.

- High gas prices tend to disproportionately harm poorer individuals and families who are operating at the margins financially.

However, there are positive aspects of high gas prices, occurring both in the short- and long-term.

Positive Impacts of High Gas Prices:

- High gas prices encourage conservation. As gas prices rise, people are more likely to find ways to minimize their driving or gas usage. This effect is immediate, but it continues to have a deeper effect in the long-term.

- High gas prices discourage vehicle and road use, which decreases the need for road construction and maintenance. This decreases costs for federal, state, and local governments alike.

- In the long-term, high gas prices promote technological innovation to reduce gas usage. When gas prices are high, the price of fuel-efficient vehicles soars, which makes it more financially rewarding for companies to develop, produce, and market these vehicles.

- On very long time scales, high gas prices will change the structure and organization of communities and society as a whole in such a way that reduces gasoline usage. For example, if gas prices remain high for a sustained period of time, living in exurbs far from employment centers will become less desirable, whereas living in urban centers will become more so. There will also be increased demand for public transportation and walkable communities, which, over time, will lead to better public transit and communities that are designed in a more walkable way.

Rising gas prices will cause the fuel-inefficient SUV on the right to fall in value, whereas it will boost the resale value of the old compact car on the left. Falling gas prices will have the opposite effect. This effect can be easily observed by browsing used vehicle sales or visiting a car dealership during times of unusually high or low gas prices.

Is there a way to implement a gas tax so as to maximize the positive effects of high gasoline prices, while minimizing the negative impacts? In order to answer this question, we need to consider something beyond just prices. People and businesses alike are not just affected by the overall price of gas, but rather, they are also affected by the fluctuations and volatility of the price of gas.

A key idea here is that the negative impacts of rising gas prices are most strongly felt immediately, whereas the positive impacts of high gas prices are only fully realized in the long run.

Volatility of Gas Prices is More Harmful than High Prices:

Most conservation decisions take time. On a day to day basis, a typical person needs to get to work, and for most Americans, this requires driving a car. While public transportation may be an option for some, it is often time consuming, and takes time to learn and familiarize oneself with. Carpooling, again, is an option for some people, but it also takes time to organize and figure out. Gasoline prices fluctuate weekly, even daily. When you drive to the gas station to find that the price of gas has jumped 50 cents from last week, there’s little you can do other than sucking it up and paying the extra money.

For business, the same is true. Logistics companies can shift to rail freight from trucks as gasoline prices make trucking less viable, but this process is slow and involved. When the prices of supplies and industrial inputs fluctuate due to shipping prices, substitute goods can be found, but this process takes even more time and is even more involved than changing shipping methods.

Gas prices that rise sharply and unpredictably thus have a much stronger negative effect both in terms of causing individual hardship and dampening economic activity, than gas prices which rise predictably over the long-run. Both people and businesses can adapt to slower, more stable gas rises. When a rise in gas prices is predictable, people and businesses can plan ahead and adapt to the change well before it happens, thus minimizing their loss.

A Floating-Rate Gas Tax:

If we implement a floating-rate tax on gasoline, we can stabilize the price of gasoline, making it predictable in the long-run. The tax can work by setting a target price for the wholesale price of gasoline, using the price of oil as a benchmark, and the tax will be equal to the difference between the market price of gasoline and the target price. The target price would be set to rise gradually, at a higher average rate than the price of gasoline was expected to rise. In the unlikely event that the market price exceeded the target price, the tax would drop to zero.

To clarify, there would be no price fixing of the price at the pump: this would be allowed to fluctuate freely. The tax would vary based on the price of oil which fluctuates on the open market, and which individual companies would have little control over, so they could not easily manipulate the tax. This regime is not perfect, and there might be some caveats about how to implement it properly, but if even a crude fit was achieved, it would offer an improvement to the current system, for reasons I will explain below.

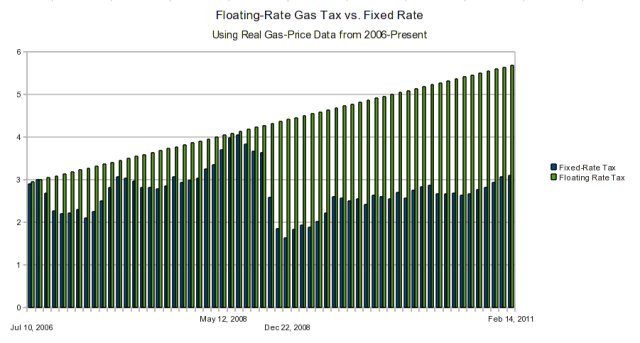

This graph shows how a floating-rate gas tax could stabilize gas prices at the pump, resulting in a steady increase (green). This graph represents a raising rate of under $3 in 5 years. The blue columns represent historical prices at the pump, from July 2006 to present, under the fixed-rate gas tax that actually existed during this time period.

Data for the graph above can be found at the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA)‘s page on U.S. Retail Gasoline Historical Prices.

There are numerous benefits of this tax regime:

- The complete predictability of the price of gasoline, resulting from such a tax scheme, would minimize the negative impact on individuals and businesses.

- Having prices rise gradually, rather than suddenly, would give both individuals and businesses ample time to adapt to the higher prices.

- The knowledge that gas prices would not fall would allow both individuals and businesses to be confident that their investment of money, time, and other resources into reducing their gas usage would pay off in the long-run, unlike under the current system where the payoff drops precipitously if gas prices fall.

- Having the target price rise faster than the average rise in the market price would minimize the chance that the market price of gas would exceed the target price, which could have a negative effect on business and individuals and would also result in a drop in tax revenues.

- Having prices rise continually over time would create strong long-term incentives for conservation, technological innovation, and sustainable community design, thus promoting sustainability and energy independence.

- Rising prices of gas would reduce the demand for and wear on roads, thus reducing government expenditures on road building and maintenance at state, federal, and local levels. This would help close budget deficits and reduce the size of government.

- Revenue for the gas tax could be used to reduce the rate of other taxes, or close the budget deficit, thus making the tax more politically viable. For example, the tax could be used to offset payroll taxes for working Americans.

Numerous others, even those whom you might expect to oppose them, strongly support floating-rate gas taxes and high gas taxes:

The idea of a floating rate gas tax is nothing new. Henry Blodget of Business Insider is a continuing advocate for a floating-rate gas tax, having written in support of such a tax just a few days ago, in the article “It’s Time For a Gas Tax“, and in a 2009 article “Time For a Gas Tax“. There are a number of high-profile individuals who have also advocated in general for a high gasoline tax. Allan Sloane, senior editor at large of Fortune magazine, in his article “Time to raise the gas tax“, provides a compelling argument that a higher gas tax, even one that is not necessarily floating, will still stablize gas prices and enable market forces to operate more efficiently.

Even Gregory Mankiw, an economist whose views I generally do not share, advocated in 2006 to raise the gas tax in his Pigou Club Manifesto; this article was published in the Wall Street Journal. In 2007, Steven Levitt, best known for his book Freakonomics, also advocated for a high gas tax in his post Hurray for High Gas Prices! Even Bob Lutz, a retired executive from General Motors, known for his stance as a global warming denier and opponent of hybrid vehicles, has advocated for higher gas tax.

Which is more important, supporting a gas tax, or making your own personal choices that promote conservation?

I cannot emphasize this next point enough:

Your own personal choices affect only a handful of others, as people may follow your example; a high gas tax affects everyone’s decisions, including people who may not care about conservation as much as you do. Furthermore, a high gas tax will reward people and businesses who are living sustainably, as it will end the subsidy to road use and gasoline use that exists under the current setup where the gas tax is not sufficient to fully pay for road expenditures, and other taxes, which you are already paying, are closing this gap.

If you care about carbon footprint, sustainability, walkability, public transportation, U.S. dependence on foreign oil, pollution, or any other environmental or social issues associated with gasoline usage, you will have the biggest impact on the world by supporting a high gas tax.

What can you do?

- Talk with people and/or write about your support of a floating-rate gas tax and a high gas tax.

- Send this post, or the other articles it links to which advocate a gas tax, to others, letting them know that you support what the post or article is saying.

- Contact politicians, voicing your support of a floating-rate gas tax and a high gas tax.

- Explain to small government advocates the ways in which a high gasoline tax can reduce the size of government by reducing road expenditures, helping close budget deficits, and allowing for reduction of other taxes.

I am, of course, in favor of higher gas taxes (perhaps partially offset by reductions in sales taxes or other taxes disproportionately paid by lower income people). I wonder about this floating point idea though- wouldn’t gas companies simply raise their prices to match whatever the set target price is?

The proposal in Business Insider is to use the wholesale price of oil as a benchmark. Oil companies could not effect the tax by changing their individual prices–the wholesale price of oil is largely out of the control of any one company, and the free market effect of this tax would be to drive prices down as demand would be driven down. This price doesn’t correspond neatly to the price at the pump, but it avoids this problem. I generally don’t like price fixing and I would like to see this tax implemented at a wholesale level, and then allow individual gas stations to set their own prices.

Gas is always going to be more expensive in some areas–not just because of taxes but because of local demand, real estate prices, and other factors. I wouldn’t ever suggest pegging the price at the pump–that would be hugely counterproductive and could lead to all sorts of problems.

The price wouldn’t be perfectly stable but it would be much more stable. Even implementing a higher flat-rate gas tax would stabilize prices…the higher the tax the more stable. But a floating-rate scheme, even if it were not perfect at matching what the market price would be, could allow more stability with a lower total amount of tax.

Hi, Alex. I hope you are still monitoring this blog, and I promise I am not stalking you, but having just recently come across you and your blogs, I am catching up on lost time as I read some of your ideas. I feel that petrol taxes should be used as a policy tool to increase the cost of gasoline. This would serve the purposes of disincentivising these fossil fuels whilst generating proceeds for alternative fuel solutions.

One of the things I have been considering for years is to embed compulsory automobile insurance into the tax at the pump. As a student of statistics, you might appreciate (apart from other factors, of course) that one might expect that the probability of getting into an accident is positively related to time driving. Denser populated areas might charge a further premium as this is another factor. Particularly accident-prone drivers may have to pay a surcharge, must as insurance premiums increase after accidents or moving violations. If a driver were interested in supplemental insurance, then that could be purchased elsewhere.

Yes, I’m still here! And I really appreciate your reading and engaging with my ideas.

I have never heard of the proposal to embed compulsory car insurance into the gas tax, but it sounds really intriguing, and appealing if it could be realistically implemented. That’s the big if. Several questions and barriers about implementation arise: is there a single-payer government system, or is there some way for individual choice and private insurers? Or is the market for private insurers only for supplemental insurance?

I think the largest barrier to that that I could think of would be the fact that different drivers pay different rates, sometimes radically different. The difference might be big enough that it could create a black market for gasoline…i.e. you tank up and then sell it to your neighbor who is paying a much higher rate because he is younger and/or has a more expensive car or more accidents.

The one thing that could be handled very easily under that system would be regional differences in insurance costs. For example, there are more costly accidents in Rhode Island than any other state, so insurance rates there are sky-high. One thing though that would not work well would be the difference in rates between cities and rural areas, as if the price difference here got too big, you’d just get more people driving farther away to tank up, or people choosing to tank up at the cheaper of work / home to evade the fee.

Hi Alex,

I agree with the actuarial issues around classes of drivers and automobiles, and perhaps a surcharge could be applied. Surcharges would tend to complicate things, but there absence may create space for moral hazard. Nonetheless, I believe that at its core, there should be a single-payer system. Unlike universal health, insurance, however, I don’t see the same need to implement this at a national level, as I don’t see the same efficiency in economies of scale that are necessary for a successful universal health insurance system. There are issues to be sure, and just what degree of coverage to be considered as compulsory becomes a key issue.

On balance, I don’t think that automobile insurance is one fee evaded by many affluent households. I feel that the ones evading this fee are lower income households, perhaps even by those driving unregistered cars in order to evade that fee, too. My goal here is to provide some basic level of protection up to some minimum amount. To be completely honest, I don’t prefer compulsory insurance for discretionary activities, but if I presume this to be a desired social policy, I feel we should create a system that minimises non-compliance. As for private markets to manage supplemental insurance, I think there is plenty of room, but all of this would be for non-compulsory insurance, penalty insurance, and gap-insurance.

In some ways, I agree that the cost and tax evasion behaviour already exists. I live and work in a suburb of Chicago. I’ve got co-workers who live in the city and commute to the suburbs—don’t ask…—, so they do try to avoid higher prices by filling their tanks in the less expensive suburbs, thereby avoiding city and Cook County taxes. This said, there may not be a large incentive to drive significantly out of my way to purchase cheaper petrol, as one would also consume more petrol trying to avoid high-density areas, say for a person who lives and works in the city.

I also agree in theory with your black market position, though, there are locations around Chicago where the difference in price is already over $0.75 a gallon (http://www.chicagogasprices.com), and no such markets exist. I am not sure where the threshold would be. The premium would need to be large enough to make it worthwhile to the middleman, and it seems that it would be tough to get any decent economies of scale.

>Your support of a high gas tax is much more important

> than your own personal conservation decisions.

Fantastic – thanks for this post.